A Text Analysis of the 4 Gospels |

19 May 2019 |

Recently I was curious about a topic in forensic linguistics: a text analysis of different perspectives on the same events. I have not studied forensic linguistics, but I was intrigued by the possibilities that I have come across in science and the media for reconstructing past facts from preserved linguistic data. In particular, I wanted to see how much two witness accounts of a set of events overlap. To do so, I used some very simple computational methods as a proof of concept.

Recently I was curious about a topic in forensic linguistics: a text analysis of different perspectives on the same events. I have not studied forensic linguistics, but I was intrigued by the possibilities that I have come across in science and the media for reconstructing past facts from preserved linguistic data. In particular, I wanted to see how much two witness accounts of a set of events overlap. To do so, I used some very simple computational methods as a proof of concept.

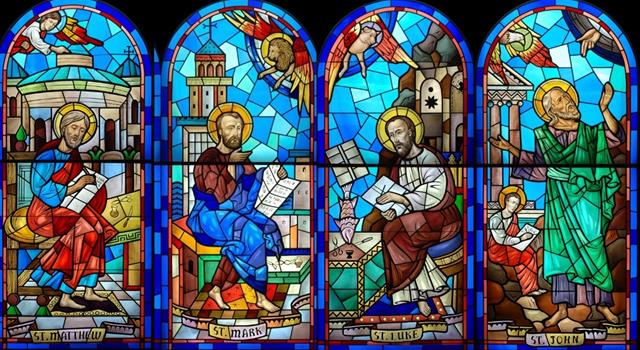

The materials I used were the 4 books at the beginning of the New Testament: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. I wanted to measure how closely they were aligned with each other. They reported on the life of Jesus Christ from different perspectives, but each had their own unique contributions to telling the stories. There are many other gospels about Christ, but these 4 were canonised. Matthew, Mark and Luke covered similar events, while John wrote about other times in Jesus’ life. Therefore the first three are called the synoptic gospels (derived from Greek for seeing together or the whole view).

To begin my analysis I obtained a text file containing the King James Version of the Bible from here, which turns out to be from the Gutenberg Project. Rather than writing a program for this task in Java, the language I am most familiar with, I decided to use this opportunity to learn more about Python. The goal of the experiment would be to

- turn the original text into a machine-readable format

- prepare a way to check how similar verses, chapters and books are

- evaluate how each gospel’s language relates to that in the other gospels

The first step of the program was achieved by reading and parsing the text file, which included

- detecting where books, chapters and verses started and ended

- tokenising the contents of each verse (naively, i.e. just using whitespace)

- ignoring punctuation, case and common words which carry little meaning

I learned a lot about Python’s iterators and generators during this step. They make it possible to read a text and stream it through the processing pipeline so that the computer’s memory is used minimally. The second step summarises that pipeline’s parts:

- creating a vector for each verse in the 4 gospels

- defining a method for computing the similarity between two verses

- aligning similar verses in two books that are being compared

Representing a word or a piece of text with a vector is a common practise in natural language processing. You define a vector space with as many dimensions as there are distinct words in the dataset, in this case the 4 canonic gospel books. To estimate how much two verses have in common I used the cosine-similarity, defined as:

The texts to which we apply this function are the Bible verses. A verse’s vector simply contains the counts for the words in that verse. So computing the cosine of the angle between two verse vectors is equivalent to measuring how much their words overlap with each other.

The third and final step was to apply this function to all verses to be compared among the 4 gospels. To be more precise, given a pair of books, the program computed the similarity score for each verse from the first book with each verse from the second book. Then, going through a list of all such verse pairs, sorted descendingly by their similarity, I aligned each verse from the first book with at most one verse from the second book. The output of this procedure can be seen in this folder, where the file matthew_mark.txt, for example, shows all verses in Matthew and, if it aligns well with a verse in Mark, the latter is shown directly underneath it with an indentation and its similarity score.

Beyond the described procedure I did not conduct any further quantitative analysis (for example assertaining the amounts and degrees of alignments). On the qualitative side, however, I was able to

- eye-ball and judge the alignments suggested by the algorithm

- find blocks of verses being aligned in a pair of books (e.g. Matthew 9:2-17 corresponds quite well with Mark 2:5-22)

- compare these outcomes with the literature on the gospels

Here are some examplary results:

The following two verses are almost identical. They are assigned a similarity score of 90% by the similarity function.

Matthew 24:32 Now learn a parable of the fig tree; When his branch is yet tender, and putteth forth leaves, ye know that summer is nigh:

Mark 13:28 Now learn a parable of the fig tree; When her branch is yet tender, and putteth forth leaves, ye know that summer is near:

These two verses, on the other hand, get a 50% rating because they only have a few words in commong (such as Master and said):

Matthew 26:25 Then Judas, which betrayed him, answered and said, Master, is it I? He said unto him, Thou hast said.

Mark 10:20 And he answered and said unto him, Master, all these have I observed from my youth.

A low rating such as 50% is adequate since these texts refer to different events. Unfortunately, it is also possible, though, for the same event to get a low alignment score, as seen here:

Matthew 25:31 When the Son of man shall come in his glory, and all the holy angels with him, then shall he sit upon the throne of his glory:

Mark 13:26 And then shall they see the Son of man coming in the clouds with great power and glory.

This pair of verses speaks about Jesus’ second coming, but is only estimated to be 56% similar, which portrays the weakness and simplicity of the involved algorithm.

Another interesting observation comes when comparing the literature on the synoptic gospels with the algorithm’s output. Articles such as this one and this one list the events mentioned in the gospels in a table which conveniently displays the relevant parallels of their contents. Many such parallels are reflected in the statistical estimates by the program, sometimes even entire blocks as mentioned above.

Finally, a check of the amount of alignments among gospels and their strengths, easily demonstrates that Matthew, Mark and Luke have a lot in common, whereas John focused his writing on other parts of Jesus’ life. That is, the synoptic nature of the first 3 gospels were confirmed in this experiment.

To view the code involved in this experiment go to this repository.